The ACCC Halt TPG Plans

TPG have shared some big dreams in the last few years – first, they announced plans to build their own mobile network in competition with the “big three”, and second, they announced plans to merge with telco giant Vodafone. The merger in particular attracted the attention of the ACCC (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission), whose job it is to ensure the market remains fair.

Recent laws silenced TPG’s plans to build their own network, so the merger looks more certain – but the ACCC have yet to make a ruling. Here’s why the merger of TPG and Vodafone could actually create further competition in the market.

The Australian mobile market

The Australian telco market offers a large number of mobile phone companies to choose from (more than 50, in fact), each offering a unique range of deals and price points. However, only three companies actually hold infrastructure – Telstra, Optus and Vodafone own the mobile networks that other companies pay to use.

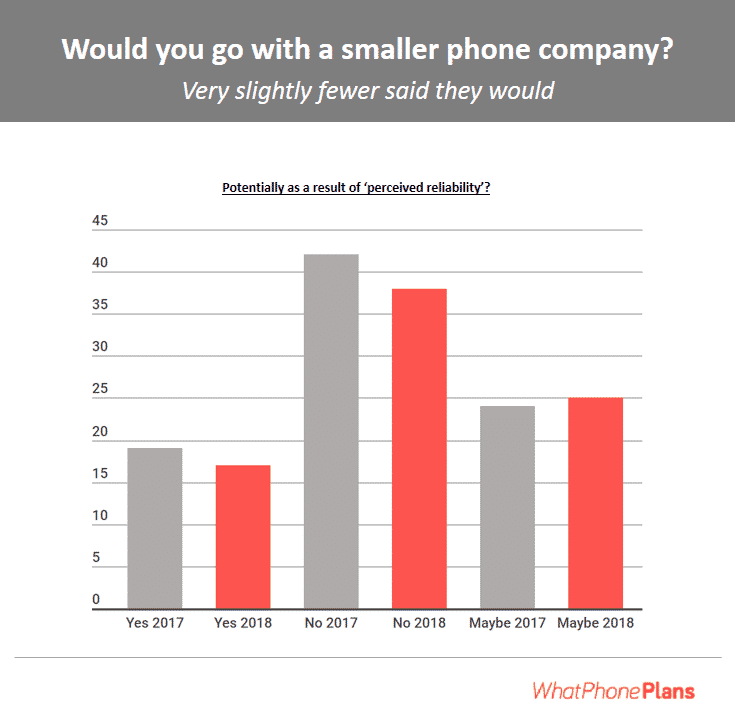

These secondary companies are called MVNOs (or mobile virtual network operators) and while they pay one of the “big three” to use their infrastructure, they often offer very competitive deals because of the much lower overhead costs, among other reasons. Even though they rarely offer better deals, the bigger companies are more likely to have other factors that attract customers, such as:

- The perception of being more reliable

- Top-range phone handsets available as part of a plan

- Deals with streaming services, sporting codes and music services that can be bundled with the plan

- TV hardware with extra channels (such as Optus Fetch or Telstra TV)

- Other inclusions such as hardware that can be added to the cost of a plan

- More money to spend on advertising, meaning more visibility

The fourth player

TPG had announced plans to launch their own mobile network, by building their own infrastructure. Previously, they had been a MVNO using Vodafone’s network. There was a mixed reaction, with most people thinking that the budget specified would not be nearly enough for even a modest network – the money that TPG had dedicated to building their network was ridiculed by Telstra as being not too far off the same amount that Telstra spends just on maintenance and upgrades for their network in a single year.

However, because TPG were not tied down by traditional expectations, they could afford to do things differently. Instead of the large cell towers usually used by mobile phone companies, TPG were planning to utilise some of their existing fixed line hardware that they used to deliver broadband, and focused on small cell technology. The stated aim was to cover 80% of Australians, with a heavy focus on urban areas. The small cell technology suggested is cheaper to buy and maintain, and could be upgraded to supply 5G when it becomes available.

Another unique approach was to forego traditional voice services and only offer data to customers. With the proliferation of other types of communication, voice calls are on the way out. However, it would take a bold customer to choose to make the move to a phone without traditional calls, so TPG planned to offer an unbeatable deal – $0 per month for the first six months, and only $10 per month after that.

So what went wrong?

TPG have recently pulled the plug on their plans to launch a network, and announced a possible merger with Vodafone. Naturally, this about-face has attracted a lot of attention. TPG faced a lot of local opposition from councils and residents that prevented them from putting up the small cells that their network plan relied on. However, the death knell for Australia’s fourth mobile network was Australia’s recent ban on Huawei involvement in 5G.

There is a great deal of suspicion surrounding Chinese telecommunication companies and equipment, as there is a perceived potential for Chinese governmental pressure to encourage security breaches if companies like Huawei are allowed to participate in setting up nationally important technology. The Chinese government has ties to the tech giant, and many countries feel that allowing them to play a role in starting up their national infrastructure is too great a risk.

With Huawei products out of the picture, TPG has abandoned its plans to build its own infrastructure. Huawei was the main supplier for TPG, as well as having cutting edge products (especially in the area of 5G) that are cheaper by a significant margin than other companies. However, TPG still has another plan in place – a potential merger with Vodafone.

TPG and Vodafone

Vodafone and TPG announced their plans for the merger on August 30th, only a week after the Huawei ban was announced, after months of serious negotiation. However, almost immediately the ACCC expressed their concerns about the deal. The issue that the Commission has with the merger is that it could reduce the number of players in the Australian telecommunications arena, reducing competition and therefore potentially leading to higher prices.

While a TPG and Vodafone merge would create a company well placed to compete with Optus and Vodafone, the ACCC concerns about the loss of competition seem misplaced. TPG has a large number of fixed-line customers and no significant presence in the mobile phone area – even had they built their network as planned. Vodafone is the third largest telco in Australia but has little impact on the fixed line section. The merge would allow each company to fill in the gaps of the other, creating a single entity that is far better placed to take on the giants Telstra and Optus.

TPG have already invested $130 million in their small cells, and have spent a considerable amount acquiring spectrum both independently and in a combined bid with Vodafone

Why the ACCC is wrong to oppose the merge

The main reason the ACCC opposed the merge was because it would mean the end to TPG plans to build their own network. However, with Huawei products off the table, TPG are unable to afford even their plans for a modest network – so the original concerns become irrelevant. But would a new network have offered enough competition to justify the ACCC’s concerns?

It is clear that the ACCC is looking in the wrong direction.

While competition is healthy and necessary, trying to increase competition at a network level is not feasible. Even the well-conceived plans and million that TPG was prepared to invest would only have been sufficient for a data-only mobile plan. The percentage of the market who would opt for a data-only phone that only works in major urban centres would have been small enough to be negligible. With TPG and Vodafone combined, the resulting company would be able to invest enough to achieve a far-reaching, quality network that could truly rival Optus and Telstra.

Ensuring Competition

There are around 50 phone companies in Australia offering different deals. There is no lack of competition or options for consumers at a service provider level – there are around twelve companies that operate just using the Optus network. The issue lies with customers being unwilling to try a new company, or use a network provider that isn’t one of the big three. Normal people are mistrustful of unfamiliar brands, with a perception that service quality can’t be as high. In fact, these companies are using the same network and often have more incentive to look after their customers than the giants.

Public policy has been inconsistent on the issue of competition. With the roll-out of the NBN, the strategy was to deliberately invest in a single, nation-wide network that was re-sold by many providers. To potentially block a billion dollar merger to encourage the development of an inferior network is a strategy that is in direct contrast to the one implemented by the NBN. A stronger company that can offer better deals themselves and a superior network to on-sell to MVNOs is surely more valuable than TPG’s original plans.

Seeking options

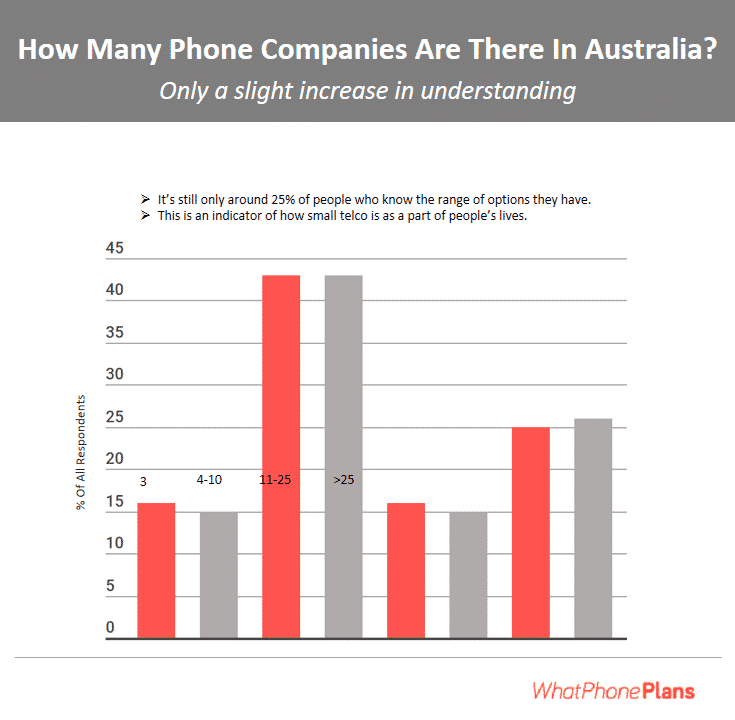

The answer to increasing competition lies mostly with customers. Some technological innovations such as the eSIM could make it easier for people to swap providers, which would provide further incentive for telcos to offer more competitive deals in order to retain customers. But as it stands, only are 25% of Australians have any idea of how many options they actually have.

As smartphones increasingly become a vital part of life, and the mobile phone bill is viewed more as the cost of a utility than an entertainment expense, customers could be persuaded to invest more time into researching their options. The ACCC blocking two companies who essentially contain two halves of the whole requirement for a modern telecommunications company is counterproductive. Supporting strong networks who can then offer their services for MVNOs to on-sell is a strategy far more consistent with public policy and more likely to result in cheaper prices for the customer in the long run.